|

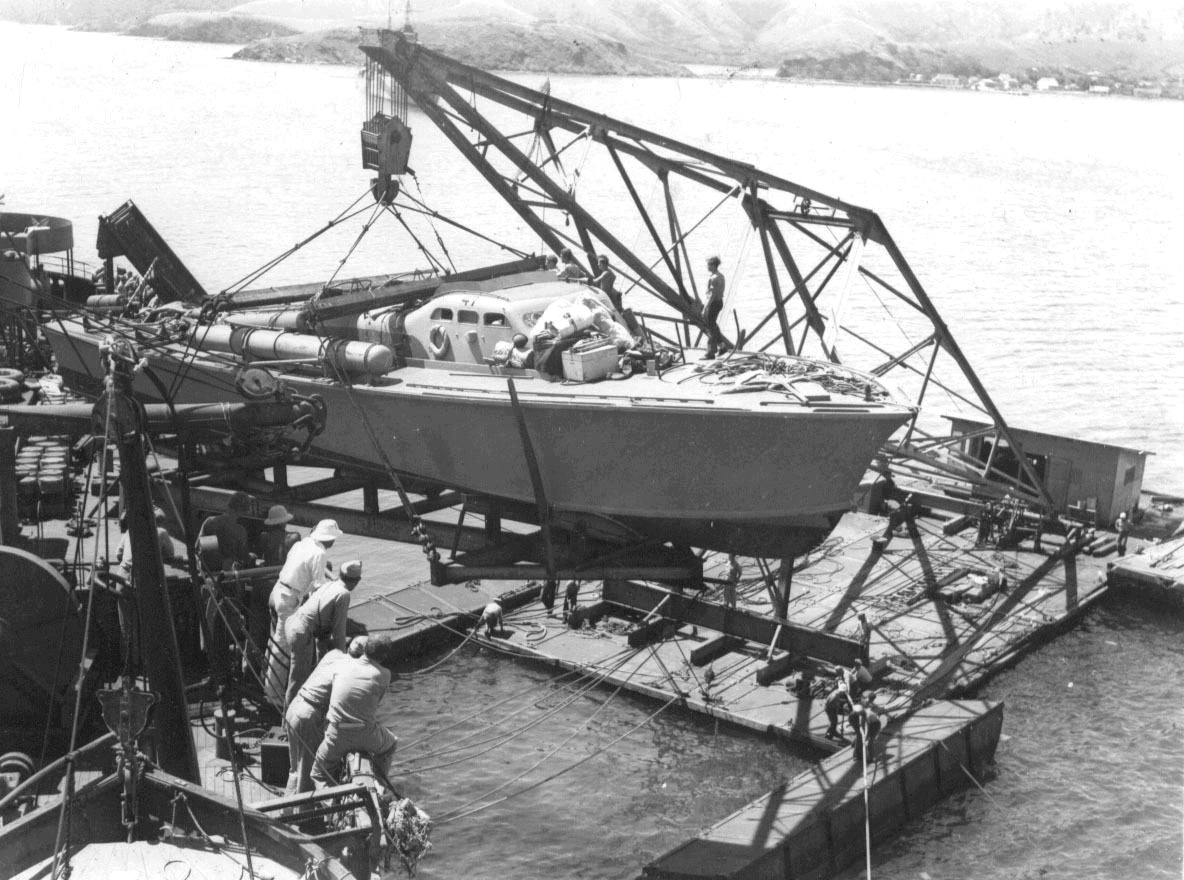

PT 109 as deck cargo aboard SS Joseph Stanton, August 1942. (National Archives)

Chapter Two: Off to War

In early August, Lieutenant Commander Farrow recieved orders to take the boats of Squadron Five to the Norfolk Navy Yard, from where they unit was loaded aboard Liberty ships and transported to Panama. After a brief stop in Guantamano Bay, the convoy reached the Panama Canal, and the boats were unloaded at the Balboa Naval Base in the Canal Zone. From there the squadron then proceeded to the new motor torpedo boat base on the island of Taboga, ten miles from the Pacific Ocean entrance to the canal. At the time the original plan was for the squadron was to go directly to the Solomons, but upon their arrival in Panama Navy brass felt that the new unit needed still more training. Squadron Five was destined to remain in the Canal Zone for another seven months; and going to the war zone in the neophyte outfit's place would be the more-experienced MTB Squadron Two. Squadron Two had tested the Navy's very first PT boats in the winter of 1940-41, and had been part of the Canal's defense force since the previous December. But there was one minor problem--because of transfers earlier that summer, Squadron Two was reduced to six boats, the Elco 77-foot PT's 36, 40, 43, 44, 47, and 59. In order to bring the unit up to strength, on September 22 six of Squadron Five's boats (PT's 109-114) were transferred to the Guadalcanal-bound 'Ron Two. Meanwhile in the United States, the man whon was to lead Squadron Two through the combat to come was in New York, busy working out engineering problems with the boats of his squadron. Lt. Rollin E. Westholm was relieved as CO of Squadron Seven, and flew to the Canal Zone to take charge of Squadron Two. Westholm, a 1934 Annapolis graduate, had been with the PT's for a long time; he was one of the original PT boat captains in the early days of the PT program, and a period in Britain studying MTB tactics used by the Royal Navy's Coastal Forces in late 1941 only added to his experience.

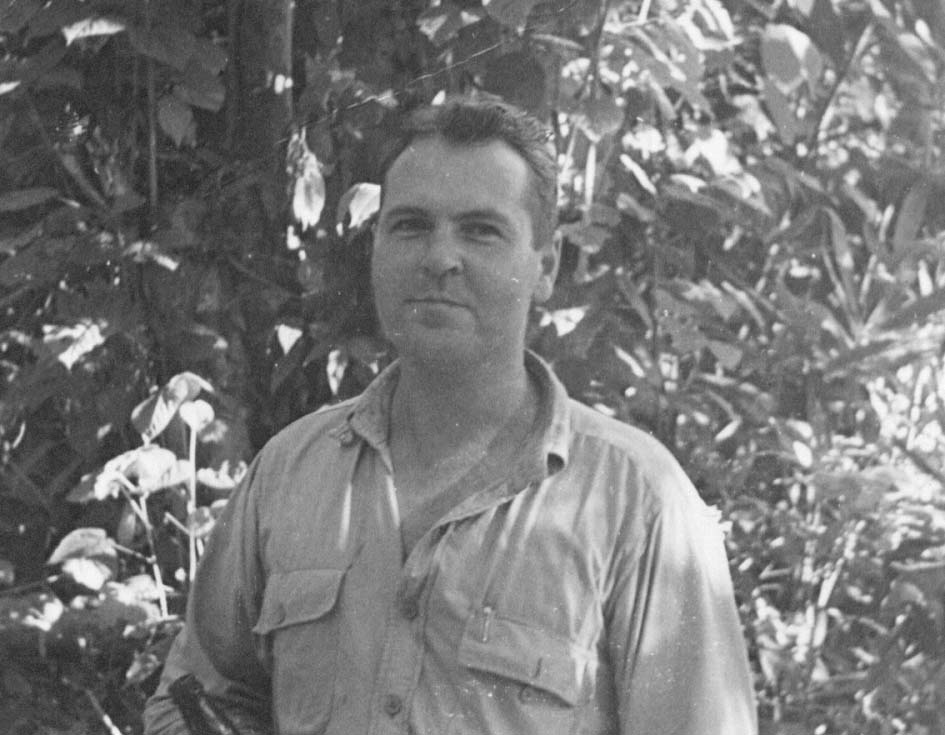

Lt. Rollin E. Westholm USN (PT Boats, Inc.)

Meanwhile in Panama, the boat transfers had initiated considerable jockeying among the squadrons for officers, men, and equipment, and PT 109 was not immune to the beehive of activity. Jack Kempner was detached from 109 by Squadron Five boss Henry Farrow, who reassigned him to another boat, leaving Bryant Larson in command. Much later, Lieutenant Commander Farrow sent Kempner to the Elco plant back in the States to watch over construction of six replacement PT's. Ensign John D. Chester was assigned a berth aboard 109 as the new executive officer, while other changes included the reassignment of fireman Joseph Hubler and torpedoman Jack Edgar. Hubler's position in the engine room was taken by James Marney; Edgar's replacement was Claude R. Dollar, TM 2/c, from PT 110.

Eight of Squadron Two's boats--the six 77-footers plus PT's 109 and 110--were readied for their sojourn to the combat theater, while the remaining four boats (PT 111-114) were to follow and join up with the squadron later. The eight boats going to the war zone were divided into two sections; the first division, with Lieutenant Westholm as senior officer was PT 36 (Lt. j/g Marvin G. Pettit), PT 40 (Lt. Allen H. Harris), PT 44 (Lt. Frank Freeland) and PT 47 (Lt. j/g Mark E. Wertz). The second section was PT 43 (Ens. James J. Cross), PT 59 (Ens. David M. Levy) PT 109 (Bryant Larson) and PT 110 (Lt. Charles E. Tilden). The first division's boats were hoisted aboard Liberty ship SS Robin Wently, while the second division was secured aboard another Liberty, SS Roger Williams. The two cargo ships departed for the Solomons on October 14, forming up with two other merchant ships and a destroyer as escort, USS Warrington. Aside from the Robin Wently's 5-inch gun crew taking target practice on an object in the water near the end of their cruise, the voyage was fairly uneventful.

Squadron Two officers on the way to the South Pacific aboard SS Robin Wently. Top row, l-r: Ens. John D. Chester USNR (XO PT 109), Ens. John C. Duckworth, Jr. USNR (XO PT 110), Lt. Charles E. Tilden USNR (CO PT 110). Bottom row, l-r: Lt. Frank Freeland USNR (CO PT 44), Ens. David M. Levy USNR (CO PT 59), and Ens. Andrew J. Floyd USNR (XO PT 43). (PT Boats, Inc.)

The convoy arrived at the harbor of Noumea, on the French possession of New Caledonia, on November 11. There the boats were unloaded, and then towed to their next destination, Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides. Two elderly destroyers of World War I vintage converted to minelayers, USS Trever and USS Zane towed the first division, leaving on November 15, and arrived at Espiritu two days later. From there two old 'four-stackers' and their charges departed on the 18th for Tulagi Harbor, 35 miles north of Guadalcanal, arriving on the 20th. Tulagi was the first PT boat operating base in the Solomons area, established in in October with the arrival of the new MTB Squadron Three, reconstituted after the original outfit was destroyed in the Philippines. Squadron Two's second division, including Ensign Larson's 109, left Noumea on the 20th, under tow of another pair of ancient four-stackers, USS Manley and USS McKean. They arrived at Espiritu on the 23rd and at 1930 that evening the convoy hoisted anchor and sailed for Tulagi. After reaching a point some 300 miles from their destination the PT's were turned loose and proceeded to complete the rest of the trip under their own power. The boats arrived at Tulagi on the 25th, tying up to the dock at the former Chinese village of Sesapi. The following day, Lieutenant Westholm came aboard 109 and took over as boat captain, while Bryant Larson reverted back to his original position as the boat's executive officer. Radioman Ed Guenther, when relating about his PT service aboard 109, said he always referred to Mr. Westholm and Mr. Larson as 'the two Swedes'. Meanwhile, Mr. Chester was transferred to "Fearless" Frank Freeland's PT 44; at the time, it seemed an insignificant move; little did anyone know later on it would prove to be fatal.

Destroyer-minelayer USS Trever (Naval History and Heritage Command)

PT 47 unloading at Noumea. (PT Boats, Inc. via Randy Finfrock)

Before Squadron Two's arrival, the PT's working out of Tulagi were the eight Elco-77's of Squadron Three:

PT 37: Lt. j/g Leonard L. Nikoloric

PT 38: Lt. j/g Robert L. Searles

PT 39: Ens. James B. Greene

PT 45: Lt. Lester H. Gamble

PT 46: Lt. Henry S. Taylor

PT 48: Lt. j/g Thomas E. Kendall

PT 60: Lt. John M. Searles

PT 61: Lt. Hugh M. Robinson (Squadron CO)

Elco 77's of MTB Squadron Three just prior to deployment to the South Pacific, August 1942. (Author's collecton via Acme Newspictures)

Like the 77-footers of Squadron Two, Squadron Three's PT's had already been in service with the Navy for over a year, and five weeks of continuous combat operations had literally left its mark on their boats. Jack Searles' PT 60 was thoroughly out of commission for the rest of the campaign from extensive damage to her bottom. Three other boats--Bob Searles' PT 38, Brent Greene's PT 39, and Hugh Robinson's PT 61--were also laid up with battle damage or from running aground in the uncharted, reef-studded waters. Jury-rigging was the order of the day; out of necessity, boats that were drydocked for repairs became spare parts kits, and the 'Ron Three men stripped them of everything useful in order to keep the operational boats running. Because of supply bottlenecks due to indifference, ignorance, or accidents in the rear areas at this stage of the war, the Tulagi-based PT's had to make do without proper repair materials, facilities, and spare parts throughout most of the Guadalcanal fighting.

When Squadron Two arrived, the fifteen operational boats were divided into two sections, to maximize the number of boats on hand to meet the Japanese. One section was dubbed the Professionals; the other was christened the Varsity. One section would go out on patrol one night, while the other section had the duty the following night. If a boat scheduled for patrol was laid up for any reason (and this happened often) the on-duty crew would borrow a boat from the off-duty section, irrespective of which squadron the boat belonged to. The borrowed boat's crew stayed ashore.

The daily routine rarely varied: after a night out looking for the Japanese, and depending on the discipline of individual boat crews, the men would usually fuel the boat up, attempt a few hours sleep, then spend a major portion of the day getting the boat back in shape for the next patrol. Chores included cleaning guns, storing ammunition, servicing torpedoes, checking and tuning the radio, and oiling the engines. The hardest job was refueling the boat--the men would haul up on deck 55-gallon gasoline drums on planks with ropes from Higgins landing craft. It took 60 drums to fill up an empty PT, and to ensure that the gas going in the fuel tanks was clean, the PT sailors hand-fueled the boat from the drums, which were strained with a chamois. If contaminated gasoline (called 'dirty gas') found its way into a PT's fuel system, the gas tanks were drained and steamed, and the engines had to be overhauled.

Air attacks while refuling the boats were an occasional worry. There weren't many air raids on Tulagi or the PT base, but if the Condition Red alarm sounded, all boats had to make for the open sea immediately. If a boat was fueling, the men simply heaved the drums overboard and got their boat underway; once the raid was over, the men had to start whole miserable, back-breaking procedure all over again once the raid was over.

Most raids were usually over Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, conducted by major Japanese air units; but two peculiar aircraft dubbed 'Maytag Charlie' or 'Louie the Louse' carried out small nuisance raids. Maytag Charlie (better known later as 'Washing Machine Charlie') earned his moniker by the unsynchronized chug-chug sound the twin engines of his old crate generated as he flew over the area'some of the men on the ground swore that it sounded like something down in the laundry. Louie the Louse was a single-engine floatplane given his nom-du-guerre (and other, more unprintable names) by the aggravated Marines. His sole purpose in life was playing the role of aerial spotter when the Tokyo Express came highballing down the Slot in bombardment mode, tossing out flares over American positions on Guadalcanal to pinpoint them for naval gunners offshore. To keep things interesting, occasionally Louie would drop a few bombs of his own.

If an Express run was expected, the PT boats patrolled a particular section of ocean in twos and threes, slowly cruising about in a somewhat rectangular search pattern, officers and men scanning the dark horizon for the tell-tale silhouettes of Japanese warships. But the Express typically preferred to make their runs on nights during the dark of the no-moon period, in order to evade the unwelcome attentions of patrolling Allied aircraft. Moonless night with cloud cover were even better--at least, from the Japanese perspective. On occasion the Express managed to approach Ironbottom Sound under cover of the heavy rain squalls prevalent in the tropics, equal to the best man-made smokescreen. To the PT sailors groping in the dark, looking to slip a torpedo into an unsuspecting Japanese warship, conditions such as these were equivalent to searching for a coal-black cat blindfolded in a darkroom. The boats were not yet equipped with radar--that wouldn't come until much later, after the campaign was over--and at times the PT crews' only warning of Japanese ships in the area was if the boat rocked back and forth in the enemy ships' wakes and they passed the PT in the night, or if a sudden flash of heat lightning enabled a lookout to briefly spot a Japanese ship's profile or the white phosphorescence of a ship's bow wave. If the enemy task force was a bombardment unit intent on shelling Guadalcanal, the American sailors could spot their targets by the flash of their heavy guns. However, this could be a disadvantage--the bright explosions from the guns also ruined the night vision of the torpedo-boat men.

When patrols weren't dangerous, they were tedious. A typical patrol lasted up to twelve hours, and peering into the darkness on alert for enemy warships for long periods of time on little sleep induced fatigue, which made it a long night indeed for the PT men, especially on those nights when the Express stayed home. On nights such as these, the boats would creep in close to the Guadalcanal shore hunting for submarines and cargo-carrying barges. The barges, slow and low slung, and hugging the coast to blend into the background, were harder to spot in the blackness than the swift-moving destroyers of the Express. With only four or five feet of water beneath their keels, the barges made poor torpedo targets and when found, were dealt with by PT gunfire; either dispatched to the deep if out at sea, or rendered unservicable for future use if discovered ashore. Submarines were a different breed--from time to time the mosquito boats would surprise an enemy sub on the surface, but the 'pigboat' usually managed to crash-dive to safety before the PT could fire off a torpedo. Since the boats were not sonar-equipped, dropping depth charges on enemy underwater craft was a hit-or-miss affair at best.

To ensure maximum speed during their battles with the Japanese, upon their arrival at Tulagi all boats were stripped of every pound of weight not essentially necessary for combat operations. All personnel lived ashore, and their gear had to be "on the beach" as well. The officers lived in native huts, while the men slept in tents. PT 109's first few patrols were quiet, but for a short time, two crews ran the boat. Lt. j/g Mark Wertz and his crew of PT 47 were without a boat of their own for some weeks after their boat had run aground on its first patrol.

When Squadron Two arrived at Tulagi, the fighting at sea had temporarily subsided. Because of the results of the climactic Naval Battle of Guadalcanal earlier in the month, the Japanese had temporarily suspended their troop and supply runs. In three days of intense, close-quarters fighting the United States Navy grappled with their Imperial Japanese counterparts in two vicious battles and a few minor skirmishes in an attempt by both sides to tip the scales of the land battle in their favor by massively reinforcing their armies ashore. The first engagement took place in the early morning hours of November 13, 1942--a Friday. A Japanese bombardment force composed of two battleships, one light cruiser, and fourteen destroyers arrived in Ironbottom Sound bent on the elimination of Henderson Field and its troublesome aircraft once and for all, so that a large convoy of Japanese transports, heavily laden with troops and cargo could arrive the next day unmolested.  To contest the Japanese juggernaut the USN could only field two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, and eight destroyers, but during a confused, savage, and horribly violent 38-minute action one of the surviving American participants described as a 'barroom brawl with the lights shot out' the numerically and materially inferior US Navy task force fought the Japanese to a draw, but managed to frustrate their bombardment mission. American naval artillery erased destroyers Akatsuki and Yudachi from the rolls of the Imperial Navy, and left battleship Hiei--her topsides riddled from shells and bullets from all calibers--a floating wreck to be sunk by American aircraft the next day. Also gone were 600 of the Emperor's finest sailors. This effort to derail the Express cost the US Navy dearly; forever gone were light cruiser Atlanta and destroyers Cushing, Laffey, Barton, and Monssen, all of which found eternal rest in the deep waters of Ironbottom Sound. Light cruiser Juneau, severely damaged during the night's fighting, was sunk by a Japanese submarine while retiring towards Espiritu Santo at eleven o'clock the morning of the 13th. Heavy crusiers San Francisco and Portland, light cruiser Helena, and destroyers Sterrett and Aaron Ward all suffered grievous damage. American dead totaled 1,439 officers and bluejackets, including the two admirals leading the force. To contest the Japanese juggernaut the USN could only field two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, and eight destroyers, but during a confused, savage, and horribly violent 38-minute action one of the surviving American participants described as a 'barroom brawl with the lights shot out' the numerically and materially inferior US Navy task force fought the Japanese to a draw, but managed to frustrate their bombardment mission. American naval artillery erased destroyers Akatsuki and Yudachi from the rolls of the Imperial Navy, and left battleship Hiei--her topsides riddled from shells and bullets from all calibers--a floating wreck to be sunk by American aircraft the next day. Also gone were 600 of the Emperor's finest sailors. This effort to derail the Express cost the US Navy dearly; forever gone were light cruiser Atlanta and destroyers Cushing, Laffey, Barton, and Monssen, all of which found eternal rest in the deep waters of Ironbottom Sound. Light cruiser Juneau, severely damaged during the night's fighting, was sunk by a Japanese submarine while retiring towards Espiritu Santo at eleven o'clock the morning of the 13th. Heavy crusiers San Francisco and Portland, light cruiser Helena, and destroyers Sterrett and Aaron Ward all suffered grievous damage. American dead totaled 1,439 officers and bluejackets, including the two admirals leading the force.

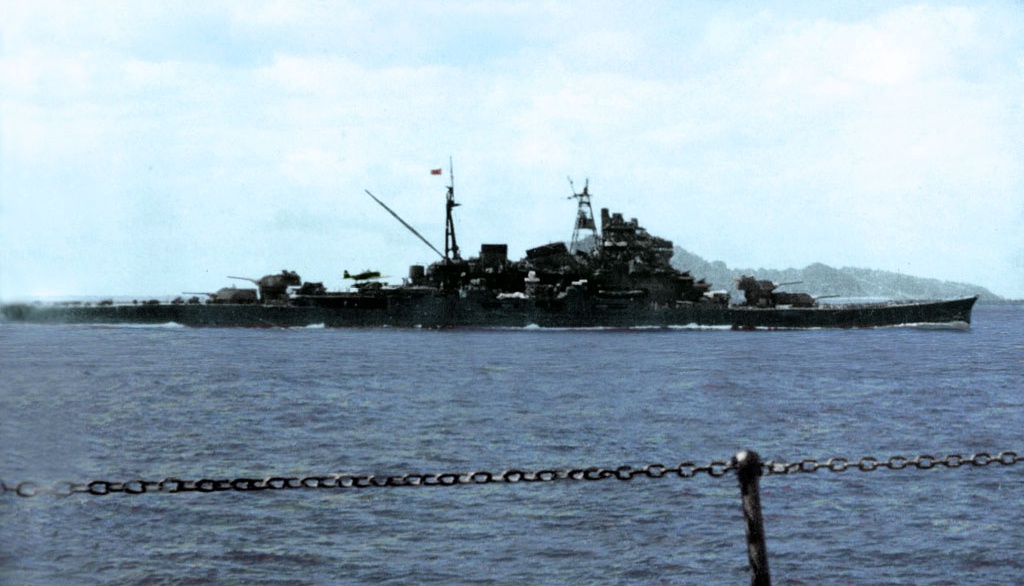

Japanese cruiser IJN Maya

The Japanese returned the night of the 13th with heavy cruisers Suzuya and Maya, escorted by several destroyers; the cruisers delivered a bomabrdment of their own, seeding the airfield with 989 8-inch shells. This time, despite setting a few aircraft afire the results were unimpressive. As a further insult, five torpedo-throwing PT’s from MTB Squadron Three persuaded the Japanese to terminate their bombardment early. The morning of the 14th surviving planes from Henderson and fresh aircraft from US carrier Enterprise sank Japanese heavy cruiser Kinugasa and also sank or seriously damaged ten of the transports with their troop reinforcements.

The ultimate clash of this three-day series on the night of the 14th culminated in a battleship duel which was a smashing victory for the United States. In one of only two battleship-versus-battleship engagements in the entire war in the Pacific, Rear Adm. Willis A. Lee, with his flag in battleship Washington along with battleship South Dakota and four destroyers as escorts, squared off against yet another Japanese bombardment force. In this final confrontation between US and Imperial Navy heavy units Ironbottom Sound claimed five more victims; Japanese battlewagon Kirishima was pummeled and left sinking by a hailstorm of steel delivered by the 16-inch rifles of Washington, while destroyer Ayanami was put out of the war by the flagship's secondary 5-inch weapons. On the American side, the services of destroyers Preston, Walke, and Benham were permanently lost to the United States Navy.

A Japanese transport grounded on the Guadalcanal shore. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

With reinforcement runs on hold, the Japanese tried developing new tactics for delivering supplies, using destroyers, submarines, and barges. Big long-range I-class submarines were simply crammed with about 16 to 20 tons of food and ammunition, and would surface off of the Japanese held portion of the Guadalcanal coastline. Barges would come from shore and quickly unload the supplies. The Japanese also sent barges filled with troops and cargo from their bases in the northern Solomons. Travelling only at night, the barges would hug the tree-lined coasts of the islands flanking The Slot during the day, to avoid Allied air reconnaisance. But fast-moving destroyers were counted on to deliver the majority of supplies. For these runs, heavy drums normally used to store gasoline or oil were painstakingly cleaned out, filled halfway with rice and barley, and loaded aboard ship. Each destroyer press-ganged into cargo duty would haul between 200 to 240 of these drums, which were joined together in clusters by ropes. Once off the island, the drums were shoved overboard close to the Japanese held coast and either pulled to the beach by soldiers waiting ashore or the tide was trusted to float them to the beach. This reduced the time a destroyer would have to lie to offshore playing the uncomfortable role of fat happy target for American heavy ships, aircraft, submarines, or motor torpedo boats. A second group of destroyers, without cargo on their decks, would act as an escort force for the supply ships. Japanese destroyers were equipped with torpedo reloads, something lacking in their Western counterparts; but weight considerations demanded any ship carrying drums had to leave their extra torpedoes ashore.

Being relegated to the role of troop and supply transport handlers did not sit well with the Japanese destroyermen, who were intensely proud of their reputation as fighting sailors; and they damned and despised these nightly runs in what a few officers were beginning to perceive was a losing cause. Captain Yasumi Toyama, chief-of-staff to DesRon (Destroyer Squadron) Two commander Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka, peevishly vented in his diary: 'We are more a freighter convoy than a fighting squadron these days--the damned Yankees have dubbed us the Tokyo Express--we transport cargo to that cursed island--what a stupid thing! Our decks are stacked high with supplies and our ammunition supply must be cut in half. Our cargo is loaded in drums which are roped together. We approach the island, throw them overboard, and run away--it is a strenuous and unsatisfying routine.' Submarine commanders and their crews were equally unhappy with their role of freight-haulers as well, sarcastically naming their trips to the island a 'Marutsu' run after the Japanese counterpart to United Parcel Service or Federal Express.

|

|

|

|

Copyright © 2002-2013 by Gene Kirkland

|